Rennes-le-Château, between mystifications and realities

by Gil Galasso from https://doi.org/10.4000/12dtr

ABSTRACT

The mystery of Rennes-le-Château has been a real foil for a historian for years. It did not survive the wave of falsifiers in the 1960s, followed by a massive arrival of sects, mediums of all kinds, who plunged this story into an inextricable esoteric maelstrom. However, there is one subject that deserves to be studied, that of a priest who, at the end of the 19th century, without having the funds, embarked on astonishing constructions in a village which had only a few inhabitants. Since then, passionate researchers have followed a hypothetical search, of a secret or a treasure. They are not academics, and the dangerous interpretations that they commit to are denounced by some historians who no longer make the effort to carry out serious research, despite the sources that do exist. In this year 2024, we try to present the actuality about of the research on what has become a myth.

Introduction

The concordists

The deniers

First part. Written sources, oral sources and first researchers (1940-1960)

Second part. Main landmarks of the life of Bérenger Saunière (1879-1917)

Renovations and discoveries

Probable discovery of a crypt under the church

Large expenses and a contested priest

The abbot sanctioned

Interpretations of the life of Abbé Saunière

Third part. Physical sources and debates between researchers

The Bulletin of the Society for Scientific Studies of the Aude, 1906

The book of Abbé Boudet

Documents from the gospels, real false "side scrolls"

The "Small Parchment"

The “Large Parchment"

The complex decoding of the Large Parchment

State of research on the comprehension of the coded sentence from the Large Parchment

The decoration of the church of Rennes-le-Château

The shape of the Devil and its position

The fresco

The murder of the priest Gélis

Some serious interpretations

Serrallonga's booty?

The treasure of the bishops of Alet?

A treasure from a cache located in the Rennes-le-Château countryside?

Conclusion

Introduction

At the beginning of the twenty-first century, the so-called "Rennes-le-Château" mystery seems definitively abandoned by historians. This subject is indeed a real pusher for serious research, as it has fallen into the meanders of mystification and esotericism. The few academics who looked into this case were immediately put off by the Castelren microcosm, which many nickname "the open-roof asylum"1. As it is assimilated to the enlightened who mix with this enigma [other] Audois delusions of all kinds, such as those associated with the much commented Bugarach peak, which would be the last shelter for humanity2, located near the place of our research.

Reading the book The decoded pseudo-history: the example of Rennes-le-Château,we notice that the author, who presents himself as a historian, considers that there is no longer any difference between serious research and esoteric delirium in this village3.

"Atlantis, megaliths, druids, Christian mythology, Cathars, Templars, secret societies or visits by extraterrestrials represent some of the inexhaustible themes of pseudo-history. A contemporary myth brings them all together: the history of the treasure of Rennes-le-Château. Subjected to strange metamorphoses, it became a symbolic treasure shrouded in religious mysteries. Constantly, new hypotheses arise, grow, intertwine and hybridize, forming an almost impenetrable forest of names, dates and places."

However, there is some serious work in the circle of researchers of Rennes-le-Château, although mainly carried out by amateur historians. Wouldn't non-university research have the right to citizenship in the march of history? Before the trend towards hyperspecialisation of the university, renowned professors did not rule it out4 and knew how to rely on amateur work when necessary.

We must define the term researcher in this specific context. The researcher, who thus defines himself unrelated to the university, is often an amateur historian, passionate about his subject, sometimes equipped with a metal detector, with a good knowledge of topography, and who collects books on the case. We will name them using this qualifier in this article.

Historian Guy Thuillier5 examines the difficulty of defining a "non-professional" historian and tries to propose a classification into three groups: in the first are teachers and curators of archives or museums who work for pleasure, outside of any career interest (which would, according to him, be frequent in the provinces). In the second group, there are retirees - engineers, doctors, administrators or notaries - with technical knowledge, life experience and free time and who do research to satisfy their passion for history, usually in a field they know well. They know how to bring together interesting materials but their interpretation is not always wise, often due to the strong proximity to the subject. The third group brings together religious, hospital directors, trade unionists, etc. who work on the history of their congregation, their hospital, their parish, their union for pleasure, but often the concern for the past is mixed with other concerns, which can lead to work that lacks impartiality. The sources we have studied are often presented by these amateur historians. It is out of respect for this work that we decided to write this article.

By striving to eliminate any element that could have been manipulated by the many mystifiers identified today, in particular Pierre Plantard6 and Philippe de Cherisey7, we will try to make a synthesis of the studies conducted over the last fifty years.

Indeed, from 1967, a publication will attract to the Razès8 a crowd of heterogeneous researchers. The Gold of Rennes by Gérard de Sède9 presents, in fictionalised form, a deception that Pierre Plantard has patiently developed, from authentic documents, much like Dan Brown will later do in his Da Vinci Code. We therefore propose, from that year, to discard all manipulated (or created) parts by considering them as false.

However, some room existed before this great mystification and we will focus on these. In addition, other parts have been in possession of the mentioned duo without them understanding the essence, and we also keep them. The original question is related to the enigma of the abbot's earnings: how was he able to have his church renovated at great expense, [as well as] half of the village, a neo-Gothic villa on the land, other buildings and gardens, including a tower and an orangery? How could he frequently receive many guests and lead a great life, only to finally die in poverty?

Rather than focusing on the village of Rennes-le-Château, we prefer to talk about the mystery of Razès. Indeed, there are several theories that deviate from the village in question. During our research, we were able to identify two communities that oppose each other, sometimes in a very virulent way, to answer this original question. We could define them by the group of "concordists" against that of "negationists" by analogy with the work of David Banon10.

The concordists

The group of Concordists aims to maintain a concordance between the discoveries of Abbé Saunière or other local abbots, his constructions and renovations, and the discovery of a fabulous treasure or a great secret. In order to explain the inconsistencies that are never completely elucidated satisfactorily, some put in place a method of permanent revision of the chronology of events. We will focus here only on the most debated hypotheses.The propositions of the Concordists are constantly changing and many hypotheses are put forward without always being supported by reliable sources. Some trails are numerous, with the statement that Abbé Saunière or a group of abbots discovered a treasure.

From the 1960s, we are looking for the treasure of the Visigoths of King Alaric II, which would have been hidden in the Razès to avoid the siege of the Frankish armies of Carcassonne in 508, and which would have included part of the treasure of the sack of Rome (410)11. However, the discovery of the Guarraza treasure, which took place near Toledo between 1858 and 1861, seems to be geographically linked to one or more places chosen by the last Visigoths to keep their treasure nearby rather than in a march close to the Frankish territory.

The bishopric of Carcassonne would have known about a cache, located near Rennes-le-Château (Redae) from the sixth century12, used in troubled periods. Bishop Sergius would have withdrawn to the village to flee the arrival of the Visigoth troops led by King Leovigild (530-586). Later, according to Louis Fedié13, this same king would have made it a stronghold14. In addition, the treasure of the Templars is mentioned because a property of this order would be located near Rennes-le-Château (Le Bezu), which would house the treasure of Jerusalem, hidden during the revolt of the year 66, which would have been discovered under the Temple Mount (a place that is now the position of the Al-Aqsa mosque) by some knights who take the name of the place in 1099.

However, following the fall of Saint-Jean-d'Acre, the Templars left the city for Cyprus15 with their goods and relics. The Grand Master of the Order of the Temple, Robert de Sablé, acquired the island then belonging to Richard the Lionheart for an amount of 2,500 silver marks. The Templars then resold the island to Guy de Lusignan who became king of Cyprus. When the order is dissolved, the property of its members is transferred to the Hospitallers of the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem16, unless some remnants are hidden in French commanderies. Some Templars were driven out of France and found refuge in Scotland thanks to the help of William de Lamberton, bishop of St Andrew, who granted them his protection in 1311. In addition, a confusion exists between the ruins of the Château de Blanchefort, located near Rennes-le-Château, and Bertrand de Blanquefort, one of the great masters of the temple (1156). They are two distinct families.

In the 1980s, the trail departed from Rennes-le-Château to be located rather in the Rennes-les-Bains countryside. More and more, there is talk of a church secret that would have been kept by a group of priests, including Father Saunière17. According to some, he received funds for not revealing it or, according to others, to participate in its coding during the renovation of his church and estate. There are references to the tomb of Mary Magdalene or Jesus, and popular books are born, such as The Sacred Enigma18 or the Da Vinci code19, creating more confusion in the region.

The deniers

The group of deniers appeared in the 1980s. Jean-Jacques Bedu throws a cobblestone into the pond with his essay: Autopsy of a myth20 which aims to explain the sudden fortune of Abbé Saunière by the simple trafficking of masses. Other authors adhere to this trend and strive to demystify the case, such as David Rossoni21, whose book rejects the hypotheses put forward by the researchers, but fails to conclude logically and satisfactorily. We will try to explain why in this article. We will strive to deal only with the facts that appear most relevant in the context of the chosen problem, i.e. those that could accompany our initial question. To do this, we will present pieces dating from before the arrival of Abbé Saunière and others prior to the 1950s.

First part.

Written sources, oral sources and the first researchers (1940-1960) share the few details that are known about Bérenger Saunière, which makes sense. During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, a village priest hardly enjoyed great interest. It is therefore not surprising that sources reporting his activities are rather rare. The abbot's correspondence books and accounting statements are kept in the departmental archives of the Aude, covering the years when Saunière lived in Rennes-le-Château from 1896 to 191722. Another source to try to apprehend the complex personality of the parish priest is the "Corbu-Captier Record": a set of documents, including fragments of the priest's diaries, held today by two residents of Rennes-le-Château, Antoine Captier, and Claire Corbu, who knew his former servant, Marie Dénarnaud (1868-1953). She entered the service of the abbot in 1891, she was also his confidant. In April 191223, Saunière made her his universal legatee (wealth and real estate). However, from 1918, she was destitute, which seems paradoxical when we imagine the wealth that the abbot has acquired. In 1942, she met Noël Corbu, an industrialist from Perpignan, and concluded a life contract with him in 1946. She was then 78 years old. During the 12 years of close ties with the Corbu family, she delivered some confidences about the life and fortune of the abbé24. She died at the age of 85.

Among all pre-war researchers (i.e. before the arrival of the mystifiers), we will focus on two personalities who seem to be authoritative in the Castelren community because their writings are included in many books dealing with the case. What remains essentially of Saunière and his contemporaries is limited to the stories of the residents of the village at the beginning of the 20th century. Some were collected by these two serious researchers, who then left written and voice work.

René Descadeillas (1909-1986) is a journalist, correspondent for the newspaper La Dépêche then librarian for the city of Carcassonne (1949) and finally curator of the city's fine arts museum in 1964. He began his investigations shortly after the beginning of the case, in the 1930s, by interviewing the local population. Although some people knew Abbé Saunière, most were only able to testify on the basis of stories reported by their parents or acquaintances26. After the masons and former choirboys, he collected testimonies related to the parish priest's servant and her relatives, allegedly witnesses of his discoveries (since she accompanied the abbot everywhere). He offers a version that, to date, has not been contested27: a numeric trail associated with a traffic in masses. He writes: "The region was always poor, despite a legend of buried treasures that defied the centuries". In particular, he collects the testimony of a family with a butcher's shop in Quillan, who claims to have been paid by Abbé Saunière in very old jewelry, considered "Visigothic".

Abbé René Mazières (1909-1988) is a priest of Razès ordained in 1935, chaplain in Pezens (Aude), vicar in Quillan (Aude) then parish priest of Villeséquelande (Aude). He is interested in the history of Abbé Saunière at the same time as René Descadeillas and also collects testimonies from the population. He was interviewed in 1979 and his testimony was published online in 201928,29,30. It is noted that the semi-directive interview method is used. It seems wise to us to make particular attention to the studies conducted by a churchman familiar with this Aude religious environment. Thus, we first propose to establish a probable chronology of Bérenger Saunière's life using these written documents and testimonies.

Second part.

Main landmarks of the life of Bérenger Saunière (1879-1917)

François -Bérenger Saunière (April 11, 1852-January 22, 1917) was ordained a priest on June 7, 1879. He was first vicar in Alet (Aude) from July 16, 1879 to 1882. Between June 1882 and 1885, he held the rank of priest in the small village of Clat before becoming a teacher at the Narbonne seminary. On June 1, 1885, at the age of 33, he was appointed a priest in the small village of Rennes-le-Château, which has about 300 inhabitants.

Access to the village is difficult because you have to climb a three-kilometer path to reach the top of the hill. Its church dedicated to Sainte Marie-Madeleine is in a great state of decay. He is paid 37 francs-gold per month31. He meets Abbé Boudet, parish priest of the village of Rennes-les-Bains located below Rennes-le-Château, who has officiated there for 19 years.

Renovations and discoveries

In November 1886, Saunière decided to renovate the church both inside and out following the recommendations of the diocesan architect Guiraud Cals32. The first modifications involving the restoration of the church floor are mentioned in a document dated June 5, 1887. In July 1887, Mrs. Marie Cavailhé, a rich benefactor of monarchist obedience, donated a new altar worth 700 francs. The work is carried out by a coffee entrepreneur from Luc-sur-Aude: ÉLIE Bot.

Three events are reported by eyewitnesses during the renovation. When moving the high altar, the workers noticed a hollow in the Visigothic pillar supporting it33. Saunière found wooden tubes34 containing documents. A few days later, when completely clearing the pillars of the altar, Saunière discovered a cavity against a wall, in which he extracted a container containing gold coins and jewelry, according to the testimonies of the workers present. The priest minimises the discovery by explaining to them that they are worthless medals. Shortly after, the pulpit, which dates from the 17th century, was also restored. The carillonneur Antoine Captier35 says he found a small glass vial containing a document in a wooden column and gave it to Abbé Saunière.

In September 1891, the workers unsealed the paving stones of the church floor to relay tiles. They discover a slab in the ground. The next day36, Sunday, September 20, the abbot called on Alphonse Rousset, a 10-year-old child, as well as other children of village. He asks for their help to move this slab that is in front of the altar of the church, it will later be called "slab of the knights" [Knights Stone]. The children notice stairs under the slab. Abbé Saunière asks them to remain silent. The removed slab is then placed facing upwards in the garden of the estate and remains there for several years, it is currently exhibited at the village museum. Despite its deterioration, it is shown to date back to the Carolingian era.

Probable discovery of a crypt under the church

It is likely that Saunière then discovered a crypt under the church, as there were in most Carolingian churches, in which tombs were placed. The existence of an underground room is attested by the parish register of baptisms, marriages and deaths from the years 1694 to 1726 (Corbu-Captier), but is the supposed crypt the tomb of the lords mentioned in the excerpt? Researchers are divided on the issue, some think it is elsewhere and communicates with the crypt through an underground33,34,36,37.

Jacques Cholet is one of the few researchers to have received permission to conduct excavations in the church of Rennes-le-Château between 1959 and 1965. His report is held by a Limoux bailiff, Maître André Gastou, who was an eyewitness to the said excavations38. Cholet scans the entire church, notices a staircase under the pulpit "which goes towards the cemetery" and finds a discharge arch located at the bottom of the wall in the apse39 located against the sacristy, suggesting a possible underground room. Finally, under the floor of the sacristy, Cholet discovers the opening of a staircase heading south. This will be the last authorised search, the DRAC40 systematically ruling out any subsequent request, as the requests are numerous and more or less serious. Based on the data from this work, researcher Paul Saussez requests an expertise from a Belgian specialised company: the presence of a cavity located three meters below the choir of the church is confirmed41,42,43,44,45.

Today, the presence of a crypt under the church of Rennes-le-Château is no longer contested, simply because the building was originally the castral chapel of the lords of Rennes and not the church that was located in another place46. Its function was among other things to receive the bodies of the deceased lords. The mere presence of a liter47, still visible today outside the church, proves this.

Large expenses and a contested priest

Abbé Saunière was suspended by the French Ministry of Worship for giving sermons hostile to the Republicans from his chair during the October 1885 elections. Between December 1, 1885 and July 1886, he resumed teaching at the Narbonne seminary. However, as he is not replaced, the villagers ask for his return. Saunière is reintegrated by the prefect of the Aude with the support of his bishop Mgr. Billiards but his political position is noticed by the Catholic Circle of Narbonne48 pro-royalist49, which counts among its members his brother Alfred Saunière50. At that time, the abbot received a donation of 1,000 gold francs51 from the widow of the Count of Chambord (pretender to the throne in the event of victory of the royalists in the 1885 elections). However, during the trial brought by his bishop, he presented accounts inflating this sum to 3,000 francs. Why this falsification by the abbot himself? Some argue that these false writings allow him to hide a hidden source of income. In1890, Abbé Saunière's servant, Marie Dénarnaud, moved with her family to the presbytery of Rennes-le-Château and lived with him.

On June 21, 1891, the blessing of the statue of Our Lady of Lourdes took place outside the church, commemorating the first communion of the 24 children of the parish. A sermon is carried out by the Reverend Father Ferrafiat, a diocesan missionary, of the family of Saint Vincent de Paul, who lives in Notre-Dame de Marceille (church located in Limoux). As local witnesses attest, the statue rests on a very old pillar that was previously the base of the altar, which bears the inscriptions Mission 1891 and Penance! Penance! This element of the early Middle Ages, with a sculpted decoration, is a vestige indicating the antiquity of the church. A pillar similar to this one is exhibited at the Narbonne52 museum. In July 1891, Saunière created a mass book (Corbu-Captier background) that contained the requests for masses that he undertook to celebrate. In September 1893, he wrote a note "stop there" which was interpreted by the researchers as the end of the real celebration of the masses and which marked the beginning of a trafficking of unhonoured masses that would persist for seven years, until January 1898. Saunière writes in one of his personal notebooks (Corbu-Captier records):

- September 21, 1891: "Excavated a tomb, letter from Granes - discovery of a tomb, in the evening rain"

- September 29, 1891: "Vu parish priest of Névian - at Gélis - At Career - seen Cros and Secret"

We specify that the so-called Gélis is a priest and Cros the vicar general of Carcassonne. Some think that Cros would have come accompanied by his private secretary, hence the use of the secret diminutive53.

At the beginning of 1891, Saunière asked the town hall for permission to fence the square in front of the church, located in the public domain "in order to raise religious but uncovered monuments, such as missions or crosses and to establish a floor". The city council gives its agreement under the condition "...that all the doors that close the entrances are provided with keys, ... and that the square is open on Sundays and public holidays, from sunrise to sunset54". At the end of 1891, Saunière took the opportunity to build a "secret" room hidden behind a library in the sacristy. It is built a few meters outside the church and is located just above the staircase that will be found later by Cholet.

From 1893, some inhabitants testify to having seen the priest and his servant, at night, go to the cemetery and manipulate graves. Saunière undertakes work that does not comply with the instructions of the town hall. Despite his promise not to build anything covered in the garden in front of the church, he asked the contractor to dig a large hole near the entrance to the cemetery. He explains that he wants to set up an underground tank to collect rainwater. The approach is surprising because Rennes-le-Château has a well nearby that always provides water. Then, he ordered the construction of a small stone house above the well, which aroused the indignation of the city council.

During the year 1895, conflicts with the local population occurred, leading to complaints made to the town hall by residents from March. According to them, the priest and his servant carried out nocturnal excavations in the cemetery. On July 14, 1895, a fact definitively threw trouble on the activities of the priest. A fire breaks out in the village and firefighters request access to the cistern but Saunière categorically refuses. The mayor (Pierre Sauzède) must intervene so that the firefighters can force the door of the house. Saunière files a complaint with the gendarmerie for "home invasion". On March 10, at a meeting of the residents, an additional complaint was presented to the mayor to denounce Saunière's actions in the cemetery54. In November 1896, the abbot charged the famous Giscard factory in Toulouse (house founded in 1855) to decorate his church with statues of saints, Stations of the Cross (for 600 francs), baptismal fonts with statues of John baptizing Jesus, a bas-relief of Jesus pronouncing the Sermon on the Mountain placed above the confessional and a devil figure supporting a benitier surmounted by angels making the sign of the cross, bearing the inscriptions BS and "Par Ce Signe Tu Le Vaincras".

All these objects were chosen by Saunière in the catalogue of the Giscard company with the exception of a few which are special requests: the devil supporting the benitier55, the angels who overcome him and the statuary intended to make a composition decorating a large fresco. Neither the 1896 edition of the Giscard catalogue nor the subsequent catalogues include these unique pieces. Only the devil's head resembles that of a statue in the catalog (the dragon defeated by Saint-Michel). We will return to the subject of church decoration later in this article. The total amount of the Giscard invoice amounts to 2,500 francs, paid by Saunière in annual tranches of 500 francs from the end of December 1897. That same year, the neighbouring municipalities of Rennes and the Bains-de-Rennes were renamed respectively Rennes-le-Château and Rennes-les-Bains. From 1897, new stained glass windows were ordered for the church, at a cost of 1,350 francs, and installed in three stages - April 1897, April 1899 and January 1900. The priest Antoine Gélis de Coustaussa, originally from the neighbouring village of Rennes-le-Château, was murdered on November 1, 1897. It seems that the relationship between Boudet, parish priest of Rennes-le-Château, and Saunière stops at that moment, without knowing whether or not there is a direct cause and effect link. Other witnesses prefer to think that Saunière's way of life was shocking to the other priests in the region and that some have decided to distance themselves from him.

According to Saunière's account books, the realisation of the decoration of the church would have cost about 16,200 gold francs, a sum four times more than that necessary for the decoration of a single church, according to some researchers56. Following the renovations and decorations, the church was again consecrated by its bishop, Monsignor Billard, on Pentecost Day 1897.

Beyond the restoration work of the church, Saunière also bought clothes for his servant Marie from the catalogue of the Samaritane in Paris, for considerable sums that are overpriced compared to the lifestyle of the local population57. Between 1898 and 1905, Saunière undertook the construction of a large estate, including the acquisition of several communal plots. This estate included a neo-Gothic villa named Bethania, a tower named Magdala (which he used as a personal library) connected to an orangery by a belvedere as well as a garden with a pool and a monkey cage - all in the name of his servant Marie Dénarnaud. The abbot sanctioned renovations of his church and his ostentatious construction plans58 in a small village do not go unnoticed and arouse hostile reactions. Several complaints were transmitted to the bishopric of Carcassonne, who had already informed Saunière of a suspicion of mass trafficking and sent him two written warnings in May 1901, reiterated in June 1903 and August 1904. In 1902, Mgr. Paul-Félix Beuvain de Beauséjour is designated as bishop of Carcassonne and suppresses the complacency enjoyed by his former bishop. In January 1909, he made the decision to move Saunière to the village of Coustouge. Saunière refused this appointment and resigned on January 28, 1909, thus becoming a free priest. On May 27, 1910, Mgr. Beauséjour triggers an ecclesiastical inquiry and establishes an official indictment mentioning three reasons: disobedience to the bishop, the trafficking of masses and the unjustified and exaggerated expenses to which the royalties of unsaid masses seem to have been devoted. To respond to these accusations, Saunière is required to attend an ecclesiastical trial. Saunière did not appear at the first hearing on July 16, 1910 or at the postponed date of July 23rd when he was convicted in absentia: he was suspended for one month and was sentenced to return the money he obtained from the alleged trafficking of masses. He also did not appear at the second hearing on August 23 but managed to attend it on the postponed date of November 5, 1910. He was then condemned "to retire to a priestly retirement home or a monastery of his choice to undertake ten-day spiritual exercises, for trafficking in masses and for accepting more money than he could say masses for". He performs his penance at the monastery of Prouille59.

On December 17, 1910, Saunière asked the Sacred Congregation of the Council of Rome to reintegrate him as parish priest of Rennes-le-Château. The congregation transmitted this request to the bishopric of Carcassonne, which in 1911 sent a strict warning to Saunière, prohibiting him from giving the sacraments60. In a letter dated February 18, 1911, the bishopric asked Saunière to produce his books of accounts no later than March 2. A commission of inquiry is created to examine Saunière's financial activities in detail. On March 13, 1911, Saunière presented 61 invoices for the renovation of his church and the construction of his estate, which totalled 36,250 francs61.

On March 25, 1911, Saunière sent the bishopric a letter of explanation explaining the origin of his finances since he became parish priest of Rennes-le-Château, as well as the list of donors, for a total amount of 193,150 francs62 (an exaggerated amount). In correspondence dating from July 14, 1911, Saunière presented a statement of the expenses necessary for the renovation of his church and the construction of his estate, estimating a total cost of 193,050 francs (always exaggerated), specifying that the Villa Béthania had cost 90,000 francs and that the Magdala Tower had cost 40,000 francs. The priest, by falsifying his accounts, thus proves, in spite of himself, that he receives sums of money from another source.62 OnOctober 4, the commission of inquiry declared that Saunière had spent only some 36,000 francs out of the 193,150 francs he claimed to have spent. They also notes that Saunière refused to cooperate in the investigation. It is necessary to organise an additional hearing where Saunière will have to present his accounts for inspection by the bishopric.63 On November 21, 1911, Saunière did not appear at the third hearing and was sentenced in absentia to three months of suspension on December 5, 1911. Although Saunière's suspension is temporary, his reinstatement depends on the ecclesiastical decision that he must "undertake the restitution in the hands of the legitimate owner and according to canon law of the property diverted by him", which the priest cannot accomplish.64 After the ecclesiastical trial, Saunière lived the rest of his life in poverty, selling religious medals and rosaries to wounded soldiers stationed in Campagne-les-Bains (Aude) during the conflicts of the First World War. Saunière also sells masses and the sums earned are used for his appeal to the Vatican on which his lawyer, Father Jean-Eugène Huguet, a doctor of canon law, is working. In May 1914, Saunière planned to build a summer house but abandoned the project because he could not afford to spend the required 2,500 francs65.

On May 10, 1918, Abbé Grassaud advised Marie Dénarnaud on the selling price of the estate, which he estimated at 200,000 francs66. However, despite the interest of some buyers, the estate will not find a buyer for several years, Marie not going through with several promises of sale.

Interpretations of the life of Abbé Saunière

Thus, depending on the thought groups mentioned above, there are several possible interpretations of Saunière's life. The trafficking of masses and the discovery of a small treasure in the crypt of the church of Rennes-le-Château are admitted by all. The real subject of discord is essentially the relationship between the sums received by the mass traffic and the sums spent by Saunière. According to the deniers, the traffic was so large that it covered the costs of Saunière throughout the work of the church and then the estate. According to René Descadeillas, he obtained 24,973 francs in 1897 (whose current value is 112,378 euros) and 75,569 francs in 1899 when traffic was at its height (current value 340,060 euros), which represented large sums at the time.

The concordists do not deny the mass traffic but minimise or justify it68. Some believe that Saunière's costs could not have been fully covered by this traffic and consider that he only ensured a better life for the abbot. Others claim that the traffic was organised by a group of abbots to allow the work of the Saunière church to be carried out so that it could participate in the coding of a religious mystery that they could not reveal in the open. Finally, others think that the mass traffic was supposed to provide for a congregation of priests for their old age (the Bethania villa was built in the project of becoming a retirement home for parish priests).70 This thought group explains Saunière's financial difficulties at the end of his life by his physical inability to go abroad to recover his bank assets.

One of the most studied documents in the Razès case is an article in the annual bulletin of the SESA71 dated 1906. It is therefore contemporary with Abbé Saunière and seems indisputable to us because it was published by an organisation with a scientific dimension. This article, written and signed by an entrepreneur from Espéraza named ÉLIE Tisseyre, recounts the visit of the members of the society to Rennes-le-Château.72 The report describes the church of Rennes-le-Château as exceptional and adorned with "fresh and laughing" paintings (Abbé Saunière is not mentioned). Then, a member observes a slab that serves as a step of stairs outside, which would date from the fifth century. This is the knights' slab updated in 1891. Later, the group describes an ancient base that supports a virgin, it is the medieval pillar of the altar reused as a support of the Virgin during the 1891 mission. In the cemetery, the group sees a slab located in a corner. They indicate that its dimensions are 1.30 meters by 0.65 meters and specify that it is engraved in a rudimentary way. In the next page of the report, a drawing is supposed to describe this same slab (fig. 1)

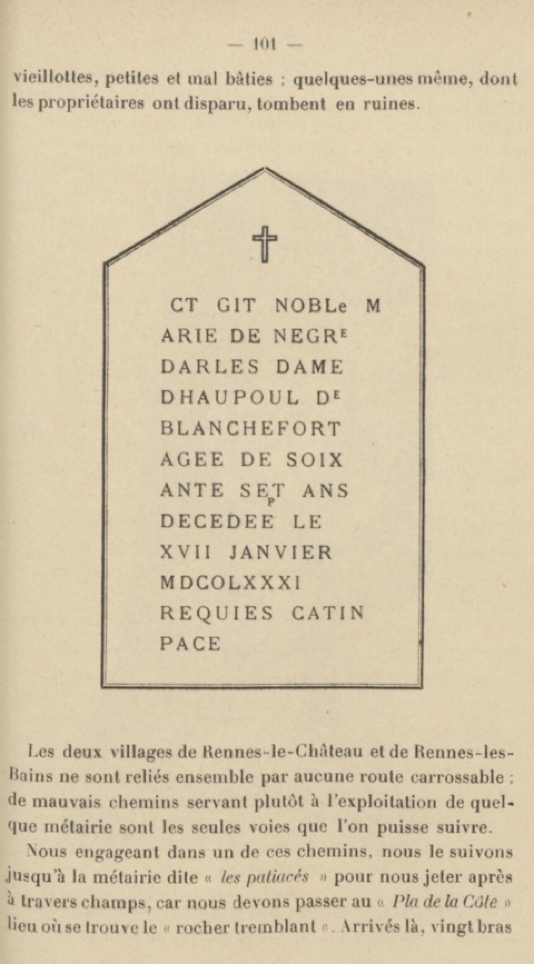

Fig. 1 Presentation of the stele of the Marquise de Blanchefort, SESA Bulletin 1906.©BnF, Gallica75

However, it seems obvious that the drawing does not correspond to the explanation of the group of members of the SESA. Indeed, the dimensions mentioned in the bulletin should correspond to a long rectangle, i.e. a slab intended to be placed on the ground above a coffin, but the drawing represents a pentagonal stele (funerary stone plate erected vertically). In addition, when we examine the inscriptions (which are not engraved superficially), we are surprised by so many inconsistencies and clumsiness on the part of the sculptor. The epitaph, properly carved, should indicate: CI GIT NOBLE MARIE DE NEGRE DABLES DAME DHAUPOUL DE BLANCHEFORT AGEE DE SIXTY-SEVEN YEARS DECEDE LE XVII JANVIER MDCCLXXXI REQUIESCAT IN PACE. Several studies show that the letters presented in miniature form the word "sword". Other inconsistencies form the word "death" (M shifted, O in a fictitious Roman encryption, R instead of B in the word of ABLES, T instead of an I in "CT GIT" instead of "CI GIT").76

The concordists immediately see the link with another piece of the enigma called the "Large Parchment" because the word Mortepe is the key to deciphering the Vigenère square that we will see later. It is strange that no serious research has been undertaken on this "dead sword", the choice of the key word seems crucial to us and should give clues on the resolution of the enigma77.

It is revealed that the stele belongs to a noble named the Marquise Marie de Negres d'Ables d'Hautpoul de Blanchefort, born in 1714 and died on January 17, 1781 at the age of 67, wife of François d'Hautpoul, Marquis de Blanchefort, who was the last lord of Rennes. It was the priest Antoine Bigou (born on April 18, 1719 in Sournia, Pyrénées Orientales), parish priest of Rennes-le-Château from 1774 to 1790, who buries the Marquise. He is one of the descendants of Jean Bigou, also from Sournia, appointed rector of the parish of Rennes in 1636.78 During the French Revolution, priests who did not support the young republic were sentenced to two years in prison and the loss of their pension by a decree of November 29, 1791. According to various sources, Antoine Bigou chose to flee to Spain, either to Sabadell or Collioure, which were then under the control of Spain, and will never return to Rennes-le-Château. It is possible that Saunière discovered documents, perhaps valuable, concealed by Antoine Bigou before his escape, a century earlier. François-Pierre Cauneille, the neighbouring parish priest of the commune of Bains-de-Rennes since 1780, also went into exile and joined his bishop in Sabadell.79

The deniers reject this piece, minimising the seriousness of the SESA, arguing that the engravers of steles and slabs of the 18th century sometimes lacked ease in spelling, and a large part of the population could neither read nor write. They produce photos of steles and slabs from the same era with similar anomalies and gross spelling errors.80 Did the slab of the tomb of the Marquise de Blanchefort exist? In the report of an engineer named Cros, a contemporary of Saunière, there is presented the diagram of a slab72 which is claimed to be the true tombstone of the Marquise de Blanchefort and the measurements correspond to those recorded by the SESA. Stories of villagers report that Saunière would have chiseled it to erase inscriptions engraved in stone.

However, we decided to remove these documents from our study because it is possible that they were handled by the Plantard-De Cherisey team. Indeed, Cros's report evokes, among other things, events that took place during the years 1958 and 1959, which cannot therefore be described by Ernest Cros, who died in Paris in 1946.

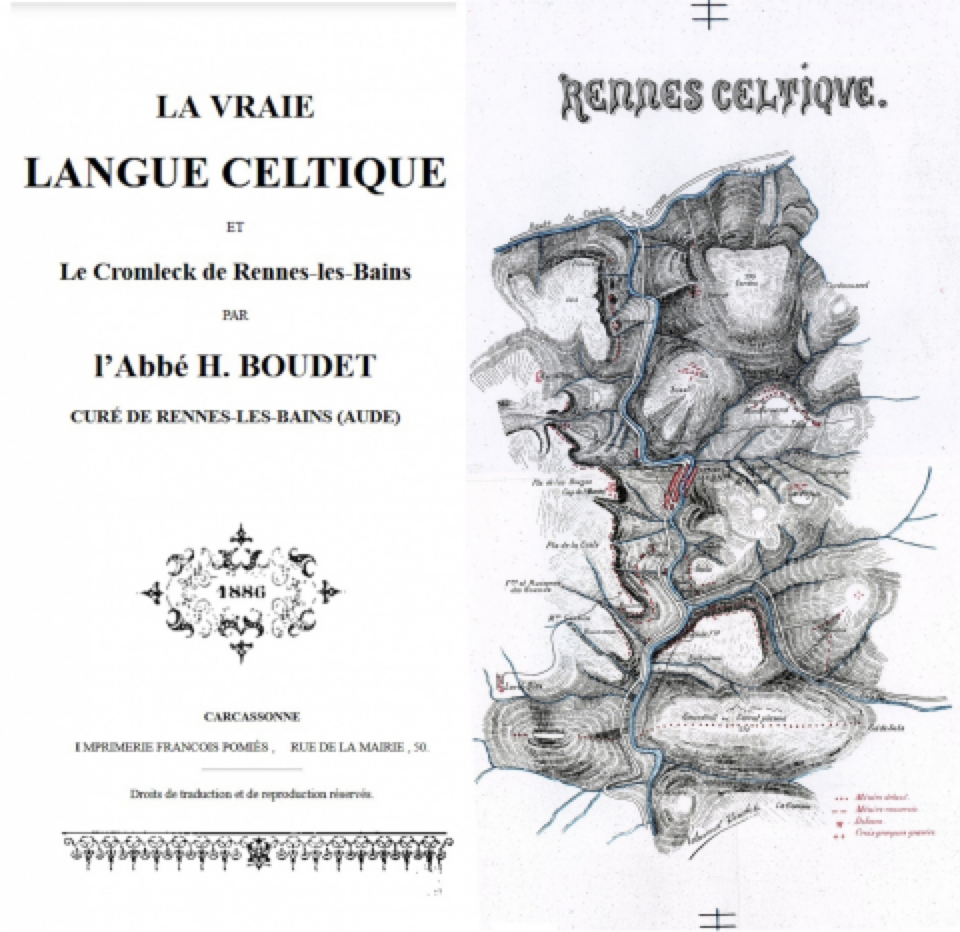

The book of Abbé Boudet

The mystery of Razès is also linked to a book written by a priest older than Saunière and who arrived in the region long before him, in 1866: Abbé Boudet, who was parish priest of Rennes-les-Bains for 42 years, a commune near Rennes-le-Château. This work, considered by some specialists as a coded book, is entitled The true Celtic language and the Cromleck of Rennes-les-Bains73 (fig. 2) It was published in 1886, the year Saunière was appointed to Rennes-le-Château. The book proposes an a priori incoherent subject, which would like modern English to be the basis of all ancient languages, a very surprising theory for a priest considered a scholar, holder of a bachelor's degree in English and member of the Society of Arts and Sciences of Carcassonne (1888). The research community is interested in Abbé Boudet's book because they think it contains explanations for finding a treasure or a secret.

Fig. 2 The True Celtic Language, by Henri Boudet, frontispiece and map of Cromleck.© Gil Galasso personal collection

Boudet rests in the Axat cemetery. On his grave is sealed a small stone book, containing a Greek engraving, "I.X.O.I.Σ", which could be understood, read backwards as a number: 310XI. However, the book contains 310 pages.

On page 11, Boudet explains that the key is the Sanskrit language, perhaps understanding the language "without writing", also called "language of birds74". Then, that the languages spoken in France, Ireland and Scotland can help us understand it. Finally, in the second chapter, he talks to us about "wheat", perhaps an allegory of gold, and evokes an ancient measure of length, (1.18 m) suppressed in 1840. It is not impossible that the coding key is contained in the footnote, which represents no apparent interest:

Other researchers interpret "I.X.O.I.Σ" as a reference to the Bible: E.C.C.I.11 for "Ecclesiastes Chap. 1 verse 1175".

The other enigma related to this book, whose author is very familiar with the region, is that it includes a map showing a chimerical cromleck76 as well as menhirs that do not exist in nature and engraved crosses represented in red. It is even more surprising that the only menhir located near the city of Rennes-les-Bains, the Peyrolles menhir, is not present on the map77. In fact, if we copy a real 1880 map under the "Boudet" map (researchers work with documents from the time of the priests), we realise that it is represented in an unusual way by a point placed following the title of the map.

The book was not well received by the local scientific communities of the late nineteenth century79. Many consider that there are too many mistakes for a scholarly author specialising in his direct universe.

The concordists are looking for a correlation between the book and the map, presumed to be coded, and the decoration of the church of Rennes-le-Château. They claim that the latter was coded to take up the elements of the book and the Boudet map. Indeed, the so-called sponsors (a congregation or a group of priests) would have deplored the complexity of the coding of the book and would then have thought of controlling the renovation of the church of Rennes-le-Château to convey a message. In the book, researchers also find many links to a coded sentence from a document called the Great Scroll, which will be studied later in this article. Many theories are proposed by various researchers. We will only mention three in this article.

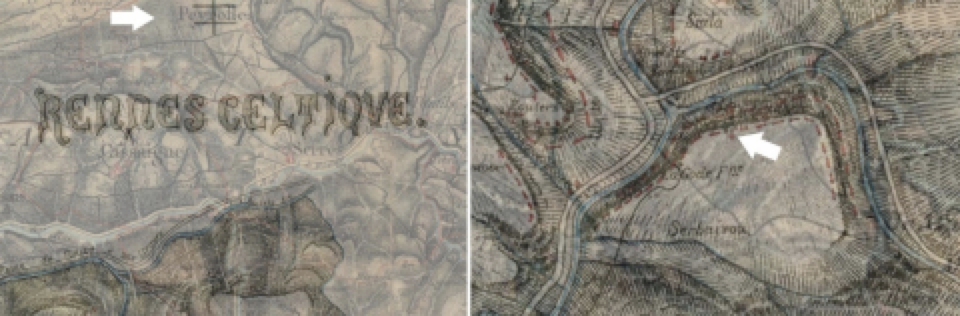

Researcher Jacques Mazières proposes an interesting theory that would liken the printing references present on the map to be necessary to modify its scale80 (fig. 3). He proposes to use the layer of a map, which he places on the Boudet map by modifying its scale so that the upper printing reference is set on the village of Peyrolles and the lower mark on that of Saint-Louis. One of the red crosses represented by Boudet on his map is then projected on the staff map and designates an area close to the confluence between the Blanque and the Sals.

Fig. 3 Study by Jacques Mazières on the Boudet81 map. The white arrows indicate the sting of an enlarged staff map on the print marks © Gil Galasso

Paul Jude's study on a relationship between the "Boudet" map and Poussin's painting "the shepherds of Arcadia83.© Gil Galasso

The researcher Raoul84 tries to prove links between Poussin and Boudet by stating that by turning the map 180 degrees, there appears, at the level of the signature, a foot on a rock identical to that of one of the shepherds of the Arcadia shepherds scene.

Other researchers believe that mathematical or geometric tools should be used and say that the key to deciphering the True Celtic Language is in its frontispiece, using the date of 1886 surrounded by direction arrows. The deniers consider that the book is not serious, which makes it a literary failure. Initially published in 500 copies, 98 units are sold while the remainder is offered to scientific communities, libraries and some notables. Today, the original book is almost untraceable and is resold for a small fortune. It has been republished. As for researchers' theories, deniers reject them as visions of the mind made of risky coincidences.

Documents from the gospels, real false "side scrolls"

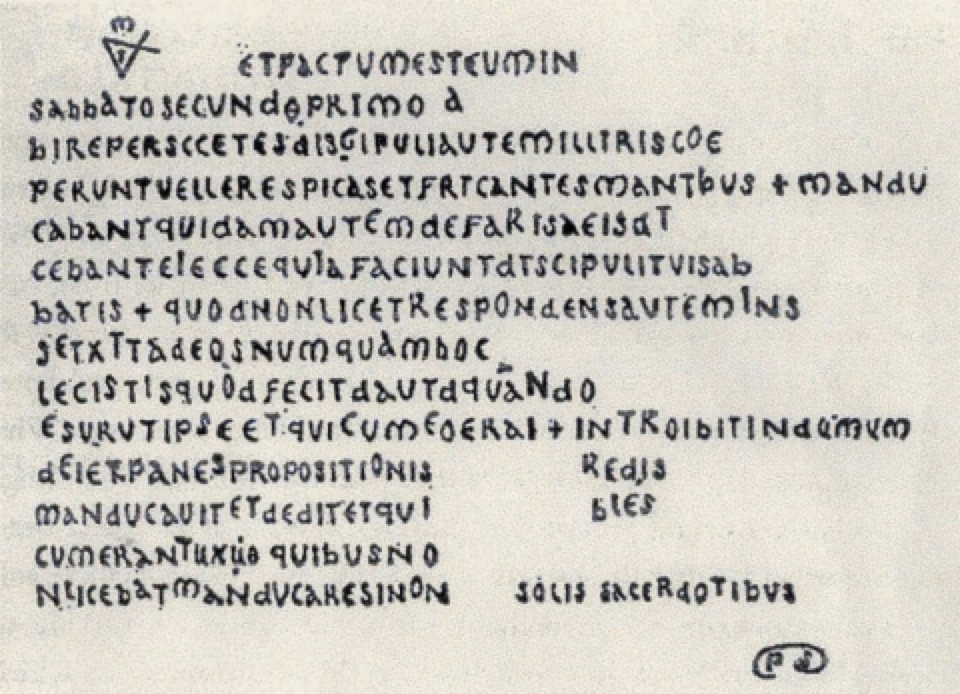

A third piece interests us, which is probably prior to the wave of falsifications that began in the 1960s. It is a set of two documents encoded from a biblical codex called the Bezae codex. These documents are wrongly called small and large parchment. They are of recent invoice and are not parchments. The originals have never been exposed to the public and their origin remains a mystery. They appear to the general public in a book by Gérard de Sède85 without their origin being authenticated. According to the concordists, the documents come from secret societies86 or from the priest who encoded the whole enigma who, at the beginning of the 20th century, would have left documents to his bishopric. Deniers say they are fakes.96 These documents are crucial in the case because their authenticity would demonstrate the presence of a secret in the Razès, while the opposite would indicate that the Rennes-le-Château case is meaningless.

The "Small Parchment"

Even if several propositions exist, the Small Parchment does not seem to have been decoded with certainty at the time we write these lines (fig. 5) The Plantard-De Cherisey team falsified the message by raising certain letters to obtain the evocation of a supposed priory of Sion associated with a Merovingian descent. After a relationship between Pierre Plantard and Philippe de Cherisey, the latter admitted to having committed this falsification87. The document contains other suspicious inscriptions, such as a signature evoking the so-called priory. In 2011, researcher Franck Daffos presented an interesting theory on a purpose of this document, which would be to indicate the name of the museum where a painting of Teniers the Younger is located necessary to decode the enigma presented in the Large Parchment (Prado Museum in Madrid).

Fig. 5 Document commonly called "the Small Parchment".© Rights reserved

The question that can arise is: Did De Cherisey falsify a coded document? Or did he build his falsification on an uncoded document? When asked about his falsification, he answers ambiguously suggesting who can say that he did not look for the original document but rather that someone would have sent it to him already coded. He declares: "The parchments were made by me, I took the oncial text from the National Library on the work of Dom Cabrol, Christian Archaeology88". However, we now know that the original text of the Parchment comes from the Codex Bezae89, copied in a dictionary of the Bible. De Cherisey therefore does not know the origin of the document he says he copied.

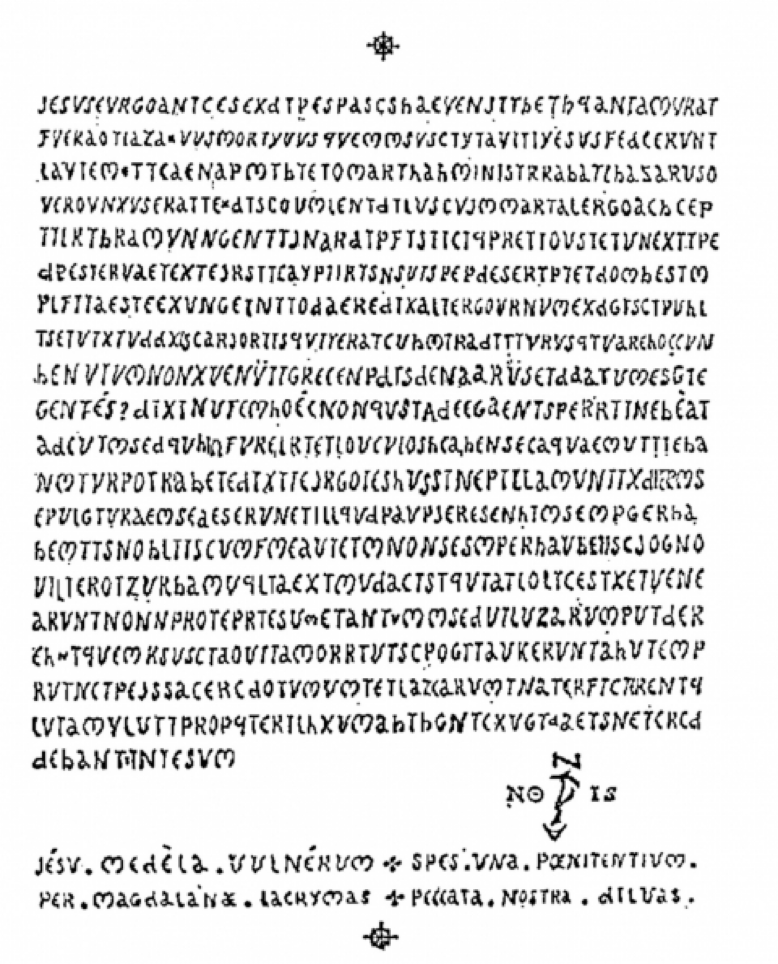

The "Large Scroll"

It is by reading the second document that we understand De Cherisey's lies and incompetence. This document, called "the Large Scroll" (fig. 6), was built from the Vulgate90, preserved in Oxford. The level of complexity of the coding eliminates any possibility of a declaration of authorship by a non-Latinist amateur.

Fig. 6 Document commonly called "the Large Parchment".© Rights reserved100

Thedocument is also taken from the gospels. Like the Small Parchment, elements were probably added to the Great Parchment by Plantard and De Cherisey as a reference to the priory of Zion, which we dismissed earlier because it is a pure invention.

The last sentence [of the Large Parchment] is directly related to the decoration of the church of Rennes-le-Château. At the bottom of the document, we find the same inscription as the one written under the altar of the church.102 The following question is therefore asked by several researchers: were the "parchments" written based on the decoration of the renovated church of Rennes-le-Château (i.e. after 1897) or was the church decorated according to the puzzle suggested on the scrolls? The first hypothesis suggests that coding dates back to the early twentieth century. In the second case, Saunière becomes the executor of an application and receives funds to carry out specific work.103

We chose not to focus on the explanation provided by Gérard de Sède because Philippe de Cherisey, in his testimony to Jean-Luc Chaumiel, fails to provide a satisfactory explanation on the coding that he himself would have created.

The complex decoding of the Grand Parchment

The text of the Large Scroll is based on chapter 12 of the Gospel of John (similar to the scene of the stained glass window behind the altar of the church of Rennes-le-Château). It is divided into two parts by the phrase "Ad Genesareth" which refers to the village of Magdala located near Lake Genesareth. Researchers have taken care to compare the parchment text to the original text. It appears that many letters have been added to the text, others have been modified or shifted and words that are reversed. We can therefore consider that the Large Parchment is encrypted.105

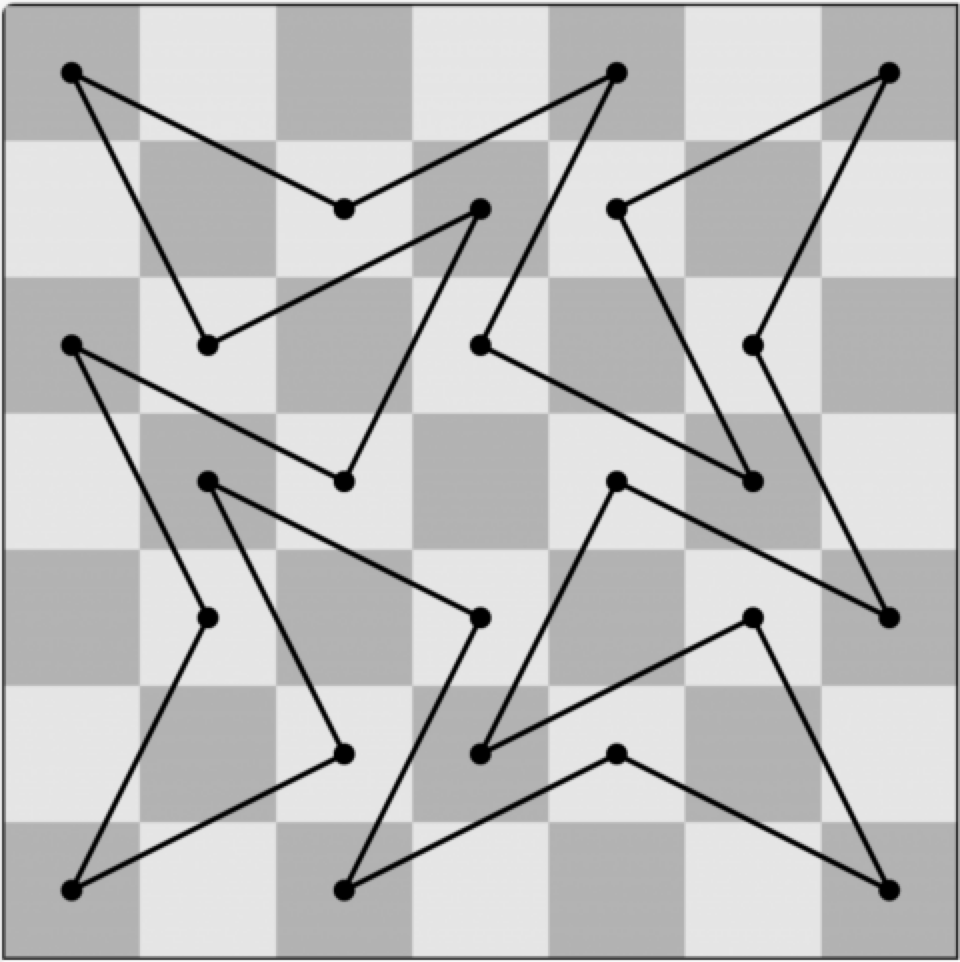

By isolating the intruding letters of the two parts of the Large Scroll, we obtain two sets of sixty-four letters, which corresponds to the number of squares present on a chessboard.106

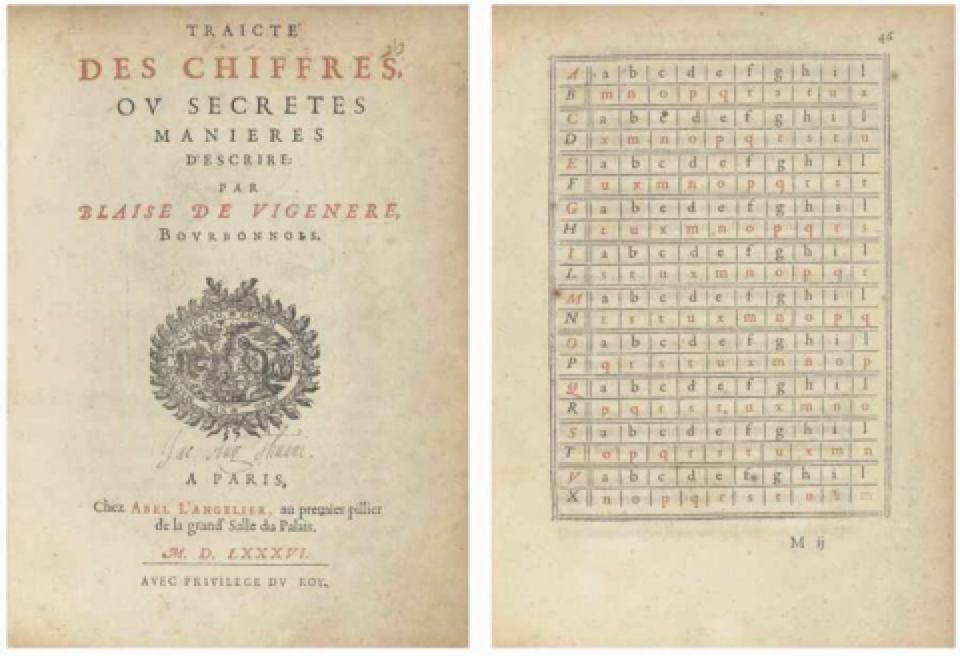

To obtain a result, the letters must be decoded beforehand using a method called "Vigenère square", a complex method of encryption by polyalphabetic substitution created by Blaise de Vigenère in the 16th century93 (fig. 7). This method uses a rectangular table of letters composed of several offset alphabets.

Fig. 7 Blaise de Vigenère, Traicté des chiffres or Secret ways of writing (1586), coding grid.©BnF, Gallica107

It is essential to use a keyword, determine the length of the key and divide the message into sections corresponding to the length of the key. In this case, it is the keyword Mortepée that must be used and it is a question, to find this key, of isolating each intruding letter placed on the famous stele of the Marquise de Blanchefort that we have previously studied.108

But if we obtain sixty-four new letters following this process, we must then consider a second decoding method by placing them on a chessboard. This method, used from the 19th century and proposed by the mathematician Euler (1707-1783), is linked to the problem of the displacement of the rider.109 The problem is whether it is possible for this piece of the game to move on a chessboard without ever returning to a box already visited. The rider moves in an L-shape, with two squares in one direction and one square perpendicular to the first direction. The challenge is to find a path that covers each square on the board. Euler solved this problem in 1759 (fig. 8).

Fig. 8 Solving the problem of Euler, direction of the jumps of the rider.© Wikipedia, personal work, royalty-free use.

After this extremely complex double decoding, we get this enigmatic sentence:"BERGERPASDETENTATIONQUEPOUSSINTENERSGARDENTLACLEFPAXDCLXXXIPARLACROIXETCECHEVALDEDIEUJACHEVECEDAEMONDEGARDIENAMIDIPOMMESBLEUES111

When we make a break of words, we get: "Shepherdess, no temptation, that Poussin Teniers keep[guard] the key, PAX DCLXXXI (681) by the Cross and this horse of God, I finish this guardian daemon at noon blue apples"112

There are several hypotheses to explain this mystery. The first hypothesis, based on negationist thought, states that this phrase is an imposture aimed at hiding a mystery that does not exist, created by the Plantard/de Cherisey duo in the 1950s. The concordists, for their part, believe that this sentence is the key to the enigma of Rennes-le-Château. Some believe that it was coded by learned priests, while others believe that it was created by a secret society.113

Researcher Franck Daffos proposes a serious hypothesis evoking the life of a Lazarist priest named Jean Jourde (1852-1930) who was a student of Fulcran Vigouroux at the seminary of Saint-Sulpice. He could be the coder.114

It is likely that the Large Parchment is linked to the inclusion of the stele of the Marquise de Blanchefort in the SESA Bulletin in 1906 because it contains the decryption key and that all the pieces were created by the same author.

State of research on the comprehension of the coded sentence from the Grand Parchment

At the time we write these lines, this enigmatic sentence is not fully deciphered. Many more or less serious proposals exist, in the form of books or videos, associated with more or less wacky theories. We present here a synthesis of the theories that seem to be the most successful.116

A first explanation proposes a reading of the sentence in the form of a funnel, that is to say that each stanza would bring the reader closer to the place to be discovered.117 The first stanza "Bergère, no temptation, that Poussin Teniers keep the key" would refer to two paintings, produced by two masters of 17th century painting: Nicolas Poussin and David Teniers the Younger.118

The first painting is identified as Les Bergers d'Arcadie (fig. 9) by Nicolas Poussin. Some recognise at the bottom of the canvas a landscape around Rennes-le-Château, others see it as a map based on landmarks prior to the earlier maps by Cassini or the "Boudet" map. A precious document is found in the case of Nicolas Fouquet, superintendent of the finances of Louis XIV, when he was seized in Saint-Mandé, in September 1661. This is a correspondence sent by his brother Louis, a priest based in Rome and close to Poussin, dated April 17, 1656, which explains the importance of having this coded painting.

Fig. 9 Nicolas Poussin, The Shepherds of Arcadia, 1640© Louvre Museum119

Near the hamlet of Pontils, near Rennes-les-Bains, there was a tomb (fig. 10) identical to the one painted in Poussin's painting, with a landscape reminiscent of this hamlet. Several books and a report from the English BBC underline this particularity. Although it was not built until the 20th century, several little-informed researchers, who thought that the tomb was the one painted in the 17th century, did not hesitate to visit it on his private land, forcing the owner to dismantle it in 1988.

Fig. 10 Rennes-les-Bains (Aude), The tomb of the Pontils in 1972.© British Broadcasting Corporation 120

Some concordists think that this tomb was commissioned by a priest or a group of priests coding the enigma to match Poussin's painting (17th century) to the coded sentence. These priests would have influenced several grieving families on the choice of a burial or an engraving, in particular by participating financially in the costs of the funeral. There is also a debate about the tomb of the priest Jean Vié, predecessor of Henri Boudet at the parish of Rennes-les-Bains regarding the amazing inscriptions on his epitaph.121 The denialists criticise this theory of a painting painted by Nicolas Poussin because he lived in Rome, never went to the Razès and did not paint outdoors. The concordists, for their part, evoke the Aude painter and French architect Jean-Pierre Rivals (Labastide-d'Anjou, Aude, 1625-Toulouse 1706). Student of A. Frédeau in Toulouse, he continued and finished his training in Rome - where he was able to meet Poussin - then returned to Toulouse as a painter and engineer of the city. He could have painted the background of the painting which would then have been completed by Poussin, this method being common in the 17th century. It seems that there is a direct link between the painting and the decoration of the church of Rennes-le-Château. In station 14 of the Way of the Cross entitled "Jesus buried", a character is identical to one of the shepherds painted by Poussin.122 The identification of the second painting suggested by the sentence is not unanimous in the circle of researchers. The majority believes that it must be one of the works of David Téniers the younger. This Flemish master often painted "Temptations of Saint Anthony". To agree with the sentence, you must therefore look for a painting that is not a temptation.123

Two paintings are particularly designated in the many studies proposed: Saint-Antoine and Saint-Paul in the desert and Saint Anthony and the seven deadly sins (figs. 11 and 12). Many arguments are in favour of one or the other of these but, in the case of more or less reasoned interpretations, we decide not to present them here. They often aim to match the landscape of the background of the painting with natural elements of the region and allegories proposed by the message delivered by the painting.

Fig. 11 David Teniers the Younger, Saint Anthony and Saint Paul in the Desert, 1660.© Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, United Kingdom

Fig. 12 David Teniers the Younger, Saint Anthony and the Seven Deadly Sins, 1670.© Prado Museum, Madrid, Spain

The rest of the sentence: "PAX DCLXXXI" has not been deciphered, in our opinion, in a sufficiently convincing way to constitute an indisputable interpretation. Some evoke a cross (pax) engraved on a rock at an altitude of 681 meters. It should be noted that Rennes-le-Château and the surrounding hills are located at about 400 m above sea level, then the altitude rises towards Mount Bugarach, to the south, which culminates at 1,230 meters. Many researchers therefore travel the mountain to look for crosses engraved on stones, probably by Abbé Boudet to corroborate his theory of imaginary Cromleck.125

The continuation of the sentence "By the Cross and this horse of God" could establish a link between the enigma and the Saint-Sulpice church in Paris because there is, near the entrance of this building, a chapel called "chapel of the angels" in which three frescoes are exhibited, works by the painter Delacroix - the fight of Jacob and the angel, Heliodorus driven out of the temple and Saint-Michel destroying the Dragon - which could correspond with all or part of the coded sentence.126

Some claim that this indication of place invites the researcher to refer to the famous "meridian of Saint-Sulpice" drawn in the same church by Jean-Baptiste Languet de Gergy, parish priest from 1714 to 1748. Indeed, this meridian, if we pursue it further south, projects near the village of Rennes-les-Bains. The saint-sulpician-type pillar capital painted on the fresco of the church of Rennes-le-Château could be a reference to this meridian.127

The end of the sentence is particularly enigmatic: "I finish this guardian daemon" refers for many to the famous devil of the benier placed at the entrance of the church of Rennes-le-Château. His particular position seems to indicate information that lends itself to many interpretations, he was baptised Asmodée, treasure keeper by the research community but no mention of this exists from the time of Saunière. A researcher proposes an association with the goddess Daemonia, goddess of the springs, in reference to a theory that the cavity sought was dug by a salty spring (the Sals River that flows in Rennes-les-Bains is so named because it is salty).128

The "blue apples" remain a mystery to this day unelucidated. Too many interpretations prevent us from presenting a theory, such as a light that would illuminate a specific place at midday through a bluish glass, blue cedar apples or elements of coats of arms of municipalities located in the region (Antugnac or Espéraza).129

Our research shows that the first pieces mentioned in coding are from the 17th century. We will see in conclusion that it is possible that a treasure comes from this time and has already been coded, perhaps through tables ordered by people with knowledge of the cache. It is then possible that these elements were taken up by one or more Sulpician priests in the 19th century to complete this coding (Delacroix painted his works around the year 1854).

The decoration of the church of Rennes-le-Château130

Endless debates oppose concordists and deniers concerning certain elements of the church decorated by Saunière. We will describe here only some of the objects and associated theories by discarding the Way of the Cross, which comes from a molding common to several churches, even if some think that it is by colouring the plasters that we are sent back to the mystery.

The shape of the Devil of the beniter and its position131

The statue of the devil (fig. 13) amazes with several elements. First of all, the position of the left hand seems to evoke a circle or an "O" and refers to the source of the circle, a place close to the village of Rennes-les-Bains. Others explain that the Devil was supposed to hold a fork, hence the position of the hand, but this tool could not have found its place in the church because it would have hindered the entrance and the fork is not mentioned in the invoice drawn up by the Giscard company.

Fig. 13 Rennes-le-Château (Aude), Marie-Madeleine church; sculpture of the devil supporting the beniter. Jcb-caz-11 © Wikipedia132

On the left wing of the devil are visible inscriptions that have not been deciphered to date.133 The posture of the Devil is commented on because he seems to be sitting on an invisible seat. However, a few meters from the previously mentioned source, a rock dug in the shape of a seat is called the "Devil's chair".134 If the devil is commonly called Asmodée, the guardian of treasures, this reference never appears from the time of Saunière.

The beniter135

Above are represented four angels who, each, evoke part of the sign of the cross.136 At the level of the beniter, a sentence challenges the visitor: "By this sign you will defeat him", which could easily be interpreted by the Christian who signs himself at the entrance of the church: by the sign of the cross you will defeat the demon in you. But the Latin phrase taken as a reference is precisely "In hoc signo vinces" which translates "by this sign you will win". Some researchers then mention the possibility that we have to defeat the treasure keeper, that is, the Devil, by drawing a cross on a map and using particular natural elements connected to each other.137 Finally, two letters are inscribed under this sentence, a B and an S. Some evoke the initials of Bérenger Saunière, who would have shown a certain megalomania by representing himself in a church that does not belong to him. Others evoke an area, near Rennes-les-Bains, of confluence between two rivers, the Blanque and the Sals.

The fresco138

With regard to the large fresco located against the back wall of the church (fig. 14), it was also the subject of a special order made by Saunière to the Giscard statuary. The scene represents a passage from the Bible: Jesus, on the Mount of Beatitudes. However, when one examines the work closely, several details are surprising.

Fig. 14 Rennes-le-Château (Aude), Marie-Madeleine church; the fresco Hawobo © Wikipedia139

If most of the characters wear first-century Sulpician-style clothes, one of them wears an outfit that seems to be from the 17th or 18th century. A bag containing bread is represented at the bottom of the hill; it is deliberately pierced. The slopes of the hill are littered with flowers. The capital of a temple or church pillar is represented lying on the right. Each of these elements, among others, has been the subject of many articles because none corresponds to the original biblical text.140

The denialists contest any church coding theory. They mention visits by priests in the 20th century who spent time examining each room of the decoration without discovering any anomaly contrasting with the dogma of the Church.

The murder of the priest Gélis141

The report of an investigating judge on the murder of Abbé Gélis de Coustaussa is the last document we decide to mention. In 1857, Antoine Gélis (1827-1897) was appointed priest of Coustaussa, a village about two kilometers from Rennes-le-Château. On November 1, 1897, at the age of 70, he was discovered murdered on the floor of the kitchen of his presbytery, dressed and wearing his parish priest's hat. As soon as the body is discovered, the mayor closes the doors of the presbytery and requests the presence of the gendarmerie. His murderers will never be found. On November 2, 1897, an investigation was opened by an investigating judge of Limoux. The report was published in 1975 by lawyers Julien Coudy and Maurice Nogué, in synthetic form in the newspaper Le Midi libre of October 3, 1975, then it was published in full in two volumes. Testimonies agree to describe the suspicious personality of the abbot, who did not give his trust. The mayor adds: "no one liked him".142 On November 1, the gendarmerie found that the head was smashed by blows to the back of the skull. The alarm system created by the abbot in the form of stretched bells was deactivated from the inside and two glasses were found on the table, suggesting that the abbot knew his murderer. The gendarmes noticed that the victim was deliberately placed in a lying position: lying on his back, arms crossed on his chest. They are surprised that the assassin has taken so many precautions to place him in this position, perhaps to offer him one last sacrament.143 Gélis' room was searched and the gendarmerie discovered a notebook containing a coding to find many silver caches inside and outside the presbytery. In all, 13,000 gold francs are discovered, or about 120,000 euros at present. We are therefore in the presence of a second rich priest, who imagined a coding to hide a fortune acquired in an unknown way. The judge was informed by the priest of Trèbes, located north of Coustaussa, that Abbé Gélis entrusted him each year with a sum of 1,000 gold francs to be placed in railway bonds.144 While Gélis has four putative heirs (nephews and nieces), his designated universal legatee is Maurice Malot, another abbot.145 Was Gélis eliminated by a congregation of which he was a part? Is it a rogue crime? The investigation is still not resolved today.

Some serious interpretations146

Some interesting clues are put forward on the origin of the treasure, if it exists, without commenting on clues prior to the seventeenth century which, to date, seem too risky to us due to lack of sources. Only one proof of this treasure allegedly discovered by the abbot was presented. It is a vermeil chalice (gold-covered silver) offered by Saunière to his friend Abbé Grassaud (1859-1946) of Saint-Paul de Fenouillet and which was publicly exposed. The Chanoine family owned it in the 1970s.147 The origin of this chalice is debated between Abbé Mazières and René Descadeillas. For the first, the cup dates from the mid-18th century and would have been offered to Abbé Saunière by the Knights of Malta. For the second, on the other hand, the chalice dates from the 17th century and would have been part of the supposed treasure found. Other testimonies evoke "old" jewelry worn by Marie Dénarnaud and members of her family, supposedly seen by the population.

Serrallonga's booty?148

At the beginning of the 17th century, a bandit named Joan Sala I Ferrer, also known as Serrallonga, ruled in Catalonia. He frequently took refuge in the city of Nyer, where Lord Thomas de Banyuls was at the head of a small army of bandits called the "Nyerros" or "bandoleros", bandits of great roads who rob travelers. After committing their misdeeds, the criminals hide on the other side of the border, on the land of the Lord of the Vivier (the current department of the Pyrénées-Orientales was not in Catalonia but in France at the time). Serralonga died at the age of 40, in 1634. However, it turns out that Baron Blaise d'Hautpoul married in 1640 a daughter of the Lord of Vivier and that Abbé Bigou comes from a village very close to Vivier. We can therefore imagine that the loot was hidden in a place known to the baron and the priest and that his initiated descendant leaves traces when leaving his church definitively to flee the revolutionary terror.

The treasure of the bishops of Alet?149

It is possible that the Rennes-le-Château countryside or its surroundings have served as a cache for various bishops of Alet. Michel Vallet's research based on documents from the "Corbu-Captier" file and interviews suggest that Abbé Saunière's secret was unraveled in the years 1937-1939 by his goddaughter Josette Barthe. At the end of her life, she showed several researchers photos of old jewelry as well as expertise documents of the same pieces by a well-known Toulouse merchant named Antonin Schwab. She explains that they came from the cache found by her great-uncle and that the store regularly came to buy these objects from Saunière.150

During her holidays at the estate during her adolescence, Josette Barthe would have found in the priest's library documents related to the revolutionary era testifying to the protection of the treasury of the bishopric of Alet. According to Michel Vallet, she also discovered forty-six gold coins from the Roman era of the quadrige type that were then sold through a priest at the Museum of Archaeology of Saint-Germain-en-Laye.151

A report by a commissioner of the young republic reveals that the inventory of Mgr. Charles de la Cropte de Chantérac (1724-1793) is particularly modest because he does not hold any valuable objects or furniture. Indeed, at the time of the inventory, he had already left the country to flee the revolution with Abbé Bigou and Abbé Cauneille. It is therefore legitimate to ask questions about the disappearance of these church properties, calyxes and furniture of the bishopric that were not mentioned in the revolutionary inventory but that did exist. The researcher Michel Azins claims to have found the trace of the people mandated to hide the ecclesiastical treasure, that is to say the nephews of the bishop, Jean Hyppolite Henri Michel de la Cropte and Louis Charles Hyppolite Édouard de la Cropte de Chantérac. These were immediately caught up in the revolutionary whirlwind, the first joining Condé's army and the second into exile in Malta.152

To support this hypothesis, some mention the surprising presence, in the Saunière library, of works of great value dating from the 18th century, presenting on the counterplate the abbot's ex-libris. However, it is attested that the bishop's library contained several thousand books before the Revolution. Researcher Michel Vallet states that the books showed signs of moisture indicating poor storage conditions for years.153

Accordingto a study conducted by researcher Patrick Mensior, Saunière held a Louis XIII armchair that would have belonged to the Bishop of Alet. Mensior compares this armchair to the detailed description of a very similar piece of furniture, owned by the bishop, described in a notarial deed of October 25, 1670.

A treasure from a cache located in the Rennes-le-Château countryside?154

The researcher Robert Thiers developed a theory from a source from the gazetier Jean Loret evoking the conflict of a bishop of Alet named Nicolas Pavillon (1597-1677) with Baron Blaise d'Hautpoul, lord of Rennes, about the sharing of a treasure found. The latter refuses to let the bishop's men "cross his land without authorisation". The researchers read in filigree the refusal that the bishop's men access an area, owned by the baron, which corresponds to a treasure cache.155 This case is closely linked to François Fouquet (1611-1673), French prelate, disciple of Saint Vincent de Paul. In 1656, he was appointed coadjutor of Claude de Rebé, Archbishop of Narbonne, with a promise of succession. At the time of the latter's death in 1659, he took over the presidency of the States of Languedoc. His brother, Nicolas Fouquet, superintendent of Louis XIV, met Nicolas Pavillon in Toulouse in 1659 in the presence of François. This interview concerned the division of the diocese of Alet, Pavilion wishing to separate Alet and his diocese from that of Limoux.156

Researcher Franck Daffos supports the theory that François Fouquet, Archbishop of Narbonne until 1673, supervised the excavation of the treasure. This circumstance would partly explain the lawsuit brought by King Louis XIV against Nicolas Fouquet about his immense fortune, the origin of which is unknown (the investigation conducted in connection with the trial did not lead to the conclusion of irregularities or embezzlement). It should be noted that Franck Daffos does not provide details on the origin of the supposed treasure.

Conclusion157

Whatcan we conclude from this research?158

Saunière was an abbot with a complex personality. It seems that funds were embezzled through a mass trafficking. It is considered that a treasure has been discovered. These two monetary sources were partially invested to renovate and beautify a church, buy communal land, build gardens and a villa to welcome retired priests (Saunière never lived in the Béthanie villa, preferring to live in a small room in the presbytery while the villa was reserved for its many guests) and enjoy a luxurious and spendthrift lifestyle that does not correspond to the usual posture of an abbot.159

WasA bbé Saunière a crook in a cassock? Was he opportunistic, ensuring a comfort of life to which no priest of the time was entitled? Although his Catholic faith does not seem refuted, did he refuse to live in the vow of poverty that the ecclesiastical dogma imposed? In this case, why didn't he reasonably save to ensure a comfortable end of life instead of the impoverishment he suffered?160Several hypotheses are raised.161 In the first place, this insoluble enigma could be a vast mystification organised in the sixties and no treasure would ever have existed around Rennes-le-Château. In this case, what meaning can be given to pieces prior to the Saunière era, which have been attested as authentic? Can the mass traffic alone justify the abbot's many expenses? This is what the deniers say.162 Secondly, an extraordinary treasure would have been discovered by Saunière in a fortuitous way. Can this explain the extravagance he showed, this luxurious lifestyle so surprising for a priest? How to explain the poverty of his end of life? Why would the source suddenly dry up during the First World War? Did the conflict prevent Saunière from withdrawing its funds abroad from 1914? Did a land collapse suddenly prevent him from accessing the cache containing his treasure (the area is known to have high seismic activity)?163

A third hypothesis assumes that a group of priests linked to the Saint-Sulpice church in Paris, or a secret congregation, would hold a church secret of which they would have left protean traces so that it would one day be discovered by peers. This theory suggests that Saunière, arrived late in this circle of "initiated" clergymen, would have received money in different forms including that of a mass trafficking orchestrated by the group itself. He would have been commissioned to renovate and decorate his church and build an estate according to precise instructions in order to continue the coding transmitted post mortem. However, a hazard could have arisen that would have prevented the fulfillment of his task - perhaps the murder of Abbé Gélis or a dispute with his bishopric or with Abbé Boudet? - leaving Saunière suddenly without resources. In this conjecture, the trafficking of masses is considered a means of guaranteeing comfort of life but it does not cover construction costs and ends at the time of the trial.164 An excerpt from the priest's notebook supports this hypothesis. On March 30, 1903, it was mentioned that he received a visit from the reverent Father Cerceau and Father Pierre Sire, parish priest of Luc-sur-Aude. He describes the visit as an "inspection" of the work, as if he had to report. We can reasonably think that, from his first discoveries, Saunière informs the congregation that commissioned him so that he would be helped in understanding the documents discovered.165

The mystery of Rennes-le-Château is undoubtedly an important element of the historical and tourist heritage of our Occitanie region. We wish to end this article by expressing the wish that it be taken up from a different angle.166 This could be the point of view of medieval history, in order to estimate the serious traces of a treasure prior to the 17th century.167or also the illumination of art history, to explore the tracks evoked by researchers on canvases and painters can be linked to this enigma.168 We will gladly make available to these explorers the sources collected by us.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

DOIs are automatically added to references by Bilbo, OpenEdition's bibliographic annotation tool. Users of institutions who subscribe to one of OpenEdition's freemium programs can download the bibliographic references for which Bilbo has found a DOI.

ADLER Alexandre, Secret Societies, Pluriel, Fayard, 2008.ANDRIEU Martial, Guiraud Cals, the forgotten architect of the city of Carcassonne, music and heritage of Carcassonne. URL:http://musiqueetpatrimoinedecarcassonne.blogspirit.com/archive/2019/10/29/guiraud-cals-l-architecte-oublie-de-la-cite-de-carcassonne-3143084.html, consulted on February 10, 2024.ARMAND Jean, Les évêques et les archévêques de France depuis 1682 à 1801, Paris et Mamers (ed.), 1891, p. 264.AZENS Michel, Rennes-le-Château, the estate of Abbé Saunière. History of its construction, information on its architect, Pegasus (ed.), 2016.BAIGENT Michael, LEIGH Richard, LINCOLN Henry, The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail, Jonathan Cape (ed), London, 1982.

BANON David, "Archaeology and Bible. In search of truth or meaning? "Pardès, 2011/2 (No. 50), p. 45-55. DOI: 10.3917/parde.050.0045. URL: https://www.cairn.info/revue-pardes-2011-2-page-45.htm.