From the Arabs to the Franks: birth of the county of Razès

It is curious to note that throughout the reign of the Merovingian kings (486-751), the region of Rennes-le-Château will never be under the control of the Franks: Septimania remains, in fact, firmly in the hands of the Visigoths, to be conquered by the Saracens from 720.

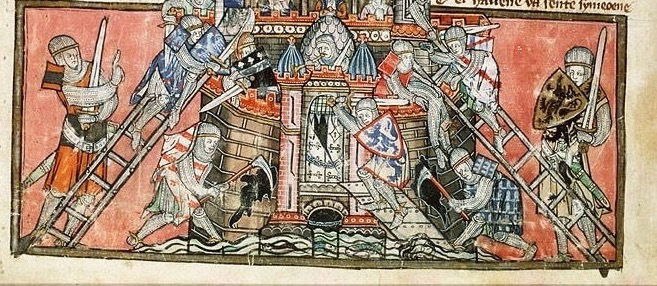

In addition to being threatened in the north by the Franks, the Visigoths suffered pressure from the west of the Arabs; after losing control of Spain in favor of the Saracens in 711, Narbonne (in 720) and Carcassonne (in 725) also fall into Arab hands.

In 752 in Soissons the Holy See, during a coronation ceremony celebrated by the Pope himself, confirms the support for King Pippin the Short. A second ceremony will be held in Saint Denis in 754. In exchange for papal support, the Franks promise support against the Lombards who are threatening to conquer Rome.Meanwhile, Septimania is firmly in Arab hands.

There is no evidence of an effective Saracen occupation of the hill of Rennes-le-Château; it is Louis Fédié who tries to fill the holes in history by reporting local hypotheses and traditions. According to the historian Pierre de Marca, also mentioned by Fédié, the archbishop of Narbonne, hunted by the Arabs, would have taken refuge right within the walls of the citadel1. This would make you think that the area was safe from Arab rule. According to a legend, however, "the Saracens founded some villariae in its surroundings and, among other things, a population center now reduced to a modest group of houses not far from Rennes-le-Château called the Maurine"2. It is difficult to disentangle between rumors and hypotheses without precise feedback.

More solid is the date of 759, in which the Franks led by Pepin the Short chase the Saracens and extend the control of the Pepinids to the whole of Septimania; it is possible that in this period the fortification of the citadel of Rennes-le-Château has become a garrison of control of the Spanish border, having repelled the Arabs through this line. As Jean Fourié writes,

'Throughout the long period that, from the eighth century leads us to the Middle Ages, the history of Rennes is practically confused with that of the county of Razès of which it was the capital [...]. Coming, as we have seen, from an ancient Roman pagus [ilpagus Redensis], the county of Razès certainly owed its "official" existence to Charlemagne, when he reorganized the administration of the Spanish marquises after having driven out the Saracens beyond the Pyrenees. [...] In the eighth century the Razès will be separated from the county of Carcassonne and integrated into the diocese of Narbonne3.

Son of Pepin the Short, in 771 Charlemagne (742-814) brought together under his power the entire Regnum Francorum - a gigantic and heterogeneous territory that goes from the Pyrenees to central Italy, to Germany. The main objective of his reign is the construction in the West of a vast Christian empire based on the ancient Roman structure. Settled in Aix-la-Chapelle, Charlemagne divided the territory into counties and dioceses and commissioned some Dominican missions to control them.

It was around 778 that the county of Razès was "born", distinct from the neighbouring ones of Carcassonne and Narbonne. More obscure is the "diocesan" condition of the territory; during an important council held in 788 in Narbonne, a certain Daniel claims the entire territory of Razès was under the control of Vuinedarius (or Winedurius), bishop of Elne. The same claim is made by the bishop of Béziers. One way to solve the problem would be to create a new diocese and make Rennes a bishopric, but the solution is opposed by many of those present. It is decided to annex the entire Razès to the diocese of Narbonne; there is a trace of this in the title of Archiepiscopus Narbonensis et Reddensis that was attributed to the archbishop of the city4.

Fédié continues: "The long wars that Pipin and Charlemagne had to fight to repel the Saracens first to the foot of the Pyrenees, then beyond this barrier, made it necessary to maintain a stronghold that would serve as an outpost on the border with Spain. Finally, when the great emperor consolidated his power, he sent royal messengers to the important cities of Septimania; these Dominican missi signaled Rhedæ to the rank of cities that deserved, so to speak, the title of royal cities"5.

This title marks a fundamental turning point in the historical investigation into the ancient Rennes-le-Château: for the first time, in fact, the name of the citadel, called Redas, is written. In 798, in fact, the bishop of Orléans, Théodulfe, and the archbishop of Lyon, Leidrade, had been sent by Charlemagne to Septimania as dominic missi, and in a document they cited Rhedae together with Narbonne and Carcassonne with these words:Inde revisentes te, Carcassonna, Redasque, Moenibus inferimus nos citò, Narbo, tuis. Undique conveniunt populi, Clerique caterva, Et Synodus Clerum, lex regit alma forum.

To report it are, among others, Claude De Vic and Joseph Vaissète in the monumental Histoire Générale de Languedoc, published in 1712 in 10 volumes. A footnote of the first volume reports the verse in question, stating that the name "Redas" refers to the "sad village of Rennes (formerly known as Règnes)"6.

1. Pierre de Marca, Marca hispanica sive Limes hispanicus, hoc est geografica et historica descriptio Cataloniae, Ruscinonis et circumjacentium populorum, t. 1, Paris, 1688 cit. in paragraph VIII in Louis Fédié, Le Comté de Razès et le diocèse d'Alet, 1880 (first chapter reproduced in Louis Fédié, Rhedae: la Cité des Chariots, Rennes-le-Château: Terre de Rhedae, 1994 now in the Italian translation by Roberto Gramolini in Indagini su Rennes-le-Château 13 (2007), pp. 631-647).

2. Paragraph VIII in Fédié 1880.

3. Jean Fourié, L'Histoire de Rennes-le-Château antérieure à 1789, Esperaza: Editions Jean Bardou, 1984, pp. 50-51.

4. Pierre Jarnac, Histoire du Trésor de Rennes-le-Château, Bélisane, Nice 1985, p. 28. Paragraph VIII of Fédié 1880 also talks about it.

5. Paragraph VIII in Fédié 1880.

6. C. De Vic, J.Vaissète, op. cit., vol.1, p. 128 (footnote). The note is signed by a certain E.B. and can date back to the first edition; the text, in fact, states that Rennes would have given the name to the Baths of Rennes, and this name dates back to at least 1709, when Don Delmas wrote a manuscript entitled Antiquités des bains de Montferrand communément appelés les bains de Rennes.