Foundation of the chapel of Santa Maria

Under Frankish control, Rhedae became a comital city. The first count of Razès was called Guillaume de Razès. For a case of homonymy, some authors have mistakenly identified him with William of Gellone (755-812), Count of Toulouse since 790, son of a certain Theodoric. Adding error to error, the father of William of Gellone is identified with Theodoric IV (713-737), son of Dagobert III, of the Merovingian dynasty1.

It was therefore Guillaume de Razès, around 778, who first settled in the castle of Rhedae. Instead, William of Gellone is remembered for the foundation in 804 of a Benedictine monastery named Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert, a few kilometers from Montpellier, where he will retire in monastic life until his death. It is probably in these years that on the foundations of the small reliquary crypt attached to the main fortress of Rhedae a small funerary chapel reserved for the counts is erected, dedicated to Santa Maria2 and decorated with ornaments equal to those found in St. Guilhem-le-Désert.

It was the archaeologist Brigitte Lescure who noticed the identical workmanship of the vestiges found in Rennes-le-Château, of evident Carolingian workmanship, and those still visible in the monastery founded by Guglielmo di Gellone. Regarding one of the two pillars3 that had been placed to support the altar, currently kept at the Village Museum, the scholar writes:

It comes from a laboratory whose activity dates back to the end of the eighth century. [...] In the north rose rose of the church of St. Guilhem-le-Désert, a choir plaque support features exactly the same interlacing decoration. [...] In 804, William erected his monastery near Aniane with artisans he had brought with him. Perhaps the same group of sculptors is at the origin of the two pieces"4.

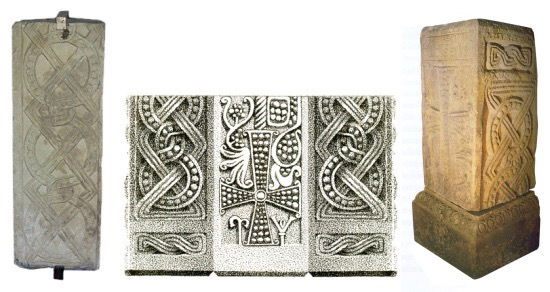

Comparison between the plate of St. Guilhem-le-Désert (left) and the engravings on the Rennes pillar (centre) in a drawing by Alain Feral and in a photograph (right).

Its dimensions are 75 x 39 x 40 cm and it shows on the main face the engraving of a patent cross decorated with some gems and stylized floral motifs. In the upper part of the drawing are represented the alpha and omega, symbols of the Christian infinity. On the two side faces appears the geometric pattern that allowed Lescure to date the piece. Very similar pillars are preserved at the Lamourguier Lapidary Museum in Narbonne, in the church of Saint Mames in Boutenac and in the church of Saint Étienne d'Oupia5.

Comparison between the engraving on the pillar of Saint Étienne d'Oupia (left) and that on the pillar of Rennes (right). Drawing by Alain Fèral.

The altar floor was fixed to the pillar by means of a lead or iron joint stuck in a small mortise engraved at the upper end of the column itself, measuring 11 x 14 x 7 cm.

The decorated pillar preserved in the village museum

The main altar consisted of a masonry slab of 210 x 60 cm6, supported in the front by two old pillars, one with a smooth surface, the other carved with the interlaid decorations cited by Lescure.

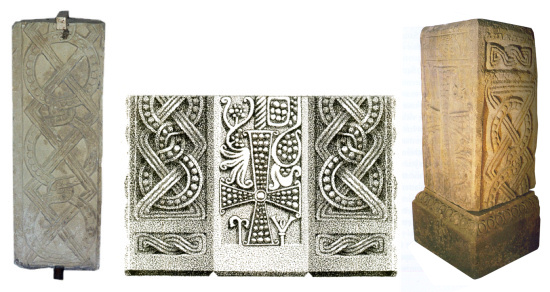

Appearance and plan of the religious building that would become the current church of Santa Maddalena (Reconstruction)

The building consisted exclusively of the apse and a short stretch of the current nave7, separated by a wall. The back of the altar slab was fixed to the wall; the small room represented by the apse was used as a sacristy. The village museum still houses one of the two baptismal fonts in which the archaeologist recognized a Characteristic decoration of the Lombard bands [...] that confirms the belonging of these baptismal fonts and the church for which they were created to primitive Romanesque art [XI sec.] [...] Height 43 cm., diameter 75 cm8.

The baptismal font kept at the village museum

In the absence of official documents attesting to the foundation of the chapel attached to the castle, the date of 798 proposed by Lescure9 can be considered more than plausible. The architect Paul Saussez confirms the esteem of the Lescure, having identified in the structure of the church the characteristic features of early southern Romanesque art10:

...the rounded apse, decorated with arches and "longobard" bands, round windows, hammer-cut stones and large mortar joints.The county passed from father to son for several decades: Guillaume de Razès (778), Béra I (796), Argila (840) and Béra II (845)11. The latter was tainted by felony and was dismissed by Charles the Bald (823-877). An act of 870 testifies to the dismemberment of the county to the advantage of the counts of Carcassonne12; this division marked the beginning of the definitive decline of the centrality of Rhedae.

1. A simple verification of the dates of birth and death of the two reveals the absurdity of this hypothesis. This is a tendentious error, because it was aimed at connecting the Merovingian lineage with the county of Razès; the hypothesis, reported as "done", will be taken up during the twentieth century precisely for this "functionality" (for example in Michael Baigent, Richard Leigh, Henry Lincoln, The Holy Grail, Mondadori, Milan 1982, p. 422)

2. Louis Fédié, Le Comté de Razès et le diocèse d'Alet, 1880 (first chapter reproduced in Louis Fédié, Rhedae: la Cité des Chariots, Rennes-le-Château: Terre de Rhedae, 1994 now in the Italian translation by Roberto Gramolini in Indagini su Rennes-le-Château 13 (2007), pp. 631-647), p. 32.

3. A complete sheet on the pillar is found in René Descadeillas, Mythologie du Trésor de Rennes, Editions Collot, 1974 (1991), pp. 131-132.

4. Cit. in Paul Saussez, Au tombeau des seigneurs (on CDRom), ArkEos, 2004, slide 45-46. See also G. J Mot, "Les autels carolingiens de l'Aude", in Fédération historique du Languedoc Méditerranéen et du Roussillon, XXXe et XXXIe Congrès, Sète-Beaucaire (1956-1957).

5. A photo of the pillar of Saint Étienne d'Oupia appears in "Un homologue de celui de Rennes-le-Château: le pilier d'Oupia", Pégase, n.3, May/August 2002, pp. 28-29, which depicts a page taken from Giry, 2001, p. 246. According to Don Giry, the pillar of Saint Étienne would have a recess in the shape of a parallelepiped, made to contain relics. Pierre Jarnac still mentions a pillar of the same style abandoned in the countryside south of Vendémies.

6. "Visite pastorale faite par Monseigneur Leuillieux dans la Paroisse de Rennes-le-Château", 1876, p. 6 (now in Patrick Mensior, Parle-moi de Rennes-le-Château, 1 (March 2004), p. 41)

7. "The apse of the church is very old, it is perhaps the only part of the old castle that still exists." (Antoine Fagès, "De Campagne-les-Bains à Rennes-le-Château", Bulletin de la Société d'Etudes Scientifique de l'Aude, Vol. 20, 1909, pp. 128-133).

8. Cit. in Saussez 2004, slide 45.

9. Brigitte Lescure, Archeological Research in Rennes-le-Château from the VIIIth to the 16th centuries, Mémoire de maitrise d'histoire de l'art, Université de Toulouse Le Mirail, 1978 cit. in Saussez 2004, slide 9.

10. Early southern Romanesque art arose in conjunction with the period of great economic and cultural momentum of the Carolingian era (752-987).

11. The list of the counts who rehed the castle of Rhedae is reported by Jean Alain Sipra in the appendix to the 1994 edition of Fédié 1880, pp. 70-71.

12. Pierre Jarnac, Histoire du Trésor de Rennes-le-Château, Bélisane, Nice 1985, p. 33.

With thanks to Mariano Tomatis for permission to translate Rennes-le-chateau.it